Larry Kornegay, Angela Ellsworth

Linear Thinking: Selections from the Permanent Collection

In so many ways, lines structure our thinking about the world. We call the contours of things around us outlines and the edge of what we can see the horizon line. Our verbal statements are written in lines of text. Our professional field is our line of work. We conceptualize order in terms of finish lines and bottom lines. […]

May 24 - Aug 24, 2014

In so many ways, lines structure our thinking about the world. We call the contours of things around us outlines and the edge of what we can see the horizon line. Our verbal statements are written in lines of text. Our professional field is our line of work. We conceptualize order in terms of finish lines and bottom lines. We reprimand each other for acting out of line. We offer information on hot lines. We save each other with lifelines.

What is a line? The English word line comes from the Old English for rope and the Latin for flax or thread—line is tactile and material. The ancient Greek mathematician Euclid defined line as a “breadthless length,” a quantity of distance without width or depth¬. Line is also theoretical and immaterial. German-Swiss artist Paul Klee said simply, “A line is a dot that went for a walk.” Line is, whether real or imagined, visual.

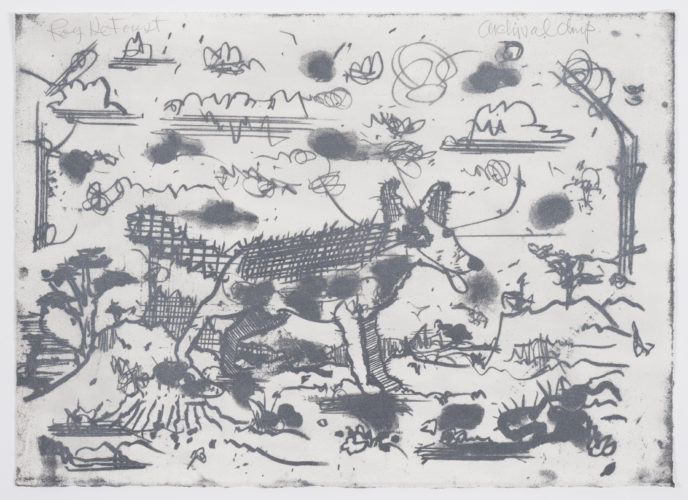

In art, line is one of the primary formal elements. Lines lead our eyes through a composition, convey information, suggest ideas, establish tone. Students of art learn that horizontal lines generate a sense of stability, diagonal lines express motion and vertical lines convey height. The words we use to describe lines are as varied and plentiful as the types artists make: sinuous and sharp, meandering and abrupt, fluid and solid, suggestive and exacting.

This exhibition presents artworks that employ line in a rich variety of ways. Sculptor George Rickey created straight lines in the form of hinged steel blades to explore motion. Photographer Mark Klett foregrounded the contour lines of saguaro cacti, their vertical trunks and outstretched arms almost assuming human qualities. Painter Deb Sokolow used angular lettering and diagrammatic lines to tell a story. Collectively, these and the other artworks in the installation encourage us to discover the conceptual and aesthetic complexity of a deceptively simple element.